Introduction to Higher Education Funding Models The sustainability, accessibility, and quality of universities and colleges are fundamentally influenced by higher education funding models. Different nations and institutions use a variety of funding strategies for higher education, each with its own benefits and drawbacks. This case study looks at a number of different funding models for higher education, how they affect students and institutions, and how they affect equity, access, and long-term viability.

Background and Importance of Funding for Higher Education:

Overview: Higher education institutions can’t function, expand, or develop without funding. It has an impact on education quality as a whole, as well as tuition rates, access to education, research opportunities, and infrastructure.

Variability worldwide: Different political, economic, and social priorities are reflected in the wide range of global funding models for higher education. The government-funded systems, tuition-driven models, and mixed funding strategies are all common models.

Contextual History:

Development: In the past, governments frequently provided funding for higher education as a public good, with students paying little to no tuition. Diverse funding models have emerged as a result of shifting economic conditions, expanding access, and rising costs over time.

Changing Trends: Global trends in higher education privatization over the past few decades have led to an increasing reliance on tuition fees, private funding, and student loans.

The Public-Funded (Government-Funded) Model:

Approach: Students in this model pay little or no tuition because higher education is mostly funded by the government. Institutions receive funding from the government based on things like enrollment, performance, and research output.

Examples:

Germany: The government provides funding for public universities, and both domestic and international students are eligible for free tuition. The public authority covers the vast majority of the functional expenses, with establishments getting subsidizing in light of understudy numbers and exploration execution.

Norway: Like Germany, Norway’s advanced education framework is government-financed, with no educational expenses for understudies. To guarantee universal access to higher education, the government provides significant funding.

Private, tuition-driven model:

Approach: Students’ tuition fees are a significant source of funding for this model’s institutions. This model is frequently used by private colleges and universities, which also make money from donations, endowments, and grants for research.

Examples:

States of America: The tuition-driven model is used by many private universities in the United States. A significant source of revenue, tuition costs vary greatly from institution to institution. Additionally, substantial endowments are used by some elite universities.

Japan: Tuition fees provide the majority of funding for Japan’s higher education system, which is dominated by private universities. Despite the fact that there are scholarships and government subsidies available, these institutions frequently charge a high tuition rate.

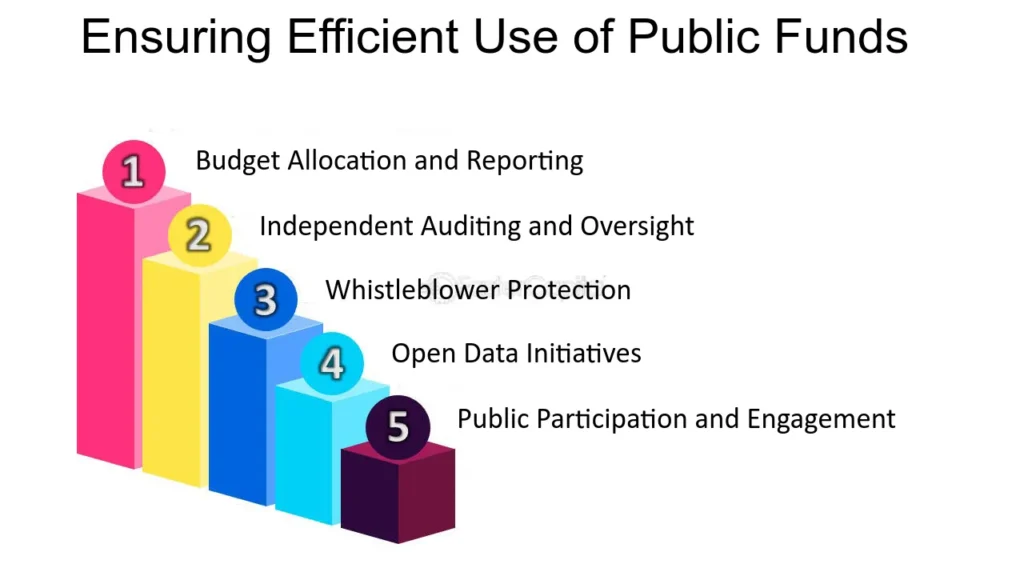

Model of Mixed Funding:

Approach: In this model, tuition fees and other sources of revenue are combined with funding from the government. This method is frequently used by public universities, with the government providing a base of funding while students contribute through tuition.

Examples:

British Isles: In the United Kingdom, universities charge tuition in addition to receiving government funding for teaching and research. In Britain, educational expenses are covered, however understudies can take out government-upheld advances to take care of expenses.

Australia: Tuition fees and contributions from the government make up the majority of the funding for higher education in Australia. Subsidies are provided by the government, and students can use the Higher Education Contribution Scheme (HECS) to defer paying tuition until they earn money.

Financing based on performance:

Approach: A portion of government funding is tied to performance-based outcomes, such as graduation rates, research productivity, or graduate employment outcomes. The point is to boost establishments to further develop execution and responsibility.

Examples:

USA: Tennessee The Tennessee Higher Education Commission uses a funding formula that is performance-based. This means that schools get money based on things like how quickly students progress, how many degrees they earn, and how well they align with the workforce.

Denmark: A portion of the funding in Denmark’s funding model is tied to the number of students who complete their degrees within the allotted time frame. This funding model incorporates elements that are performance-based.

Successes and Achievements Equity and Accessibility:

Model Powered by the Government: By eliminating tuition fees, countries like Germany and Norway have ensured that students from all socioeconomic backgrounds can pursue higher education without facing financial obstacles.

Impact: Higher enrollment rates, lower student debt, and greater social mobility are all outcomes of public investment in higher education.

Institutional Independence and Advancement:

Model Driven by Education: Due to their reliance on tuition, endowments, and private donations, private institutions in the United States have been able to maintain their autonomy and invest in cutting-edge programs, facilities, and research.

Impact: The adaptability in financing has permitted these organizations to answer rapidly to changing instructive necessities and market requests, frequently prompting the advancement of state of the art projects and exploration drives.

Sustainable Funding in Balance:

Blended Subsidizing Model: The UK and Australia have figured out how to offset government support with educational expenses, giving establishments a steady income base while as yet offering monetary guide and credit projects to help understudies.

Impact: Institutions have been able to maintain high standards of education and research while ensuring that a wide range of people can still attend higher education.

Criticisms and Challenges Rising Student Debt and Tuition:

Model Driven by Education: The reliance on tuition fees has resulted in significant increases in the cost of education and high levels of student debt in nations like the United States. Students’ long-term financial burden and the possibility of reduced access to higher education have come under scrutiny as a result.

Impact: Rising educational cost can make hindrances for low-pay understudies and add to imbalances in admittance to advanced education. Elevated degrees of understudy obligation can likewise have more extensive monetary ramifications, influencing graduates’ capacity to buy homes, save for retirement, or put resources into additional schooling.

Public Investments and Sustainability:

Model Powered by the Government: In countries where higher education is fully funded by the government, there are concerns about how long the funding will last in the face of tough economic times, rising enrollment, and increased demand for higher education.

Impact: Spending plan limitations can prompt cuts in financing for advanced education, influencing the nature of training, research yield, and the capacity of foundations to all around the world contend.

Pressure on Performance:

Financing based on performance: Even though performance-based funding aims to increase accountability, it can also result in unintended outcomes, such as educational institutions prioritizing short-term outcomes over long-term objectives or ignoring aspects of education that are not measurable.

Impact: Institutions may be encouraged to focus on easily quantifiable metrics as a result of this strategy, possibly at the expense of more general educational goals like encouraging creativity, critical thinking, and social responsibility.

Future Directions: Examining Other Methods of Funding:

Direction: There is a growing interest in investigating alternative funding strategies that strike a balance between public investment and private contributions, reduce student debt, and guarantee sustainability over the long term.

Consideration: As potential alternatives to traditional tuition and loan models, models such as income share agreements (ISAs), in which students agree to pay a percentage of their future income for a predetermined period after graduation, are gaining attention.

Increasing Access and Equity:

Direction: It is still a top priority to make sure that students of all socioeconomic backgrounds can get into higher education. Policymakers are investigating ways of expanding monetary guide, grants, and designated help for underrepresented gatherings.

Consideration: To achieve this objective, governments and institutions may need to strengthen financial aid systems, expand outreach programs, and address structural inequality.

Promoting International Competitorship:

Direction: Funding models that help institutions compete globally, attract top talent, and participate in international research collaborations are needed as higher education becomes increasingly globalized.

Consideration: In order to maintain their competitiveness on a global scale and foster innovation, nations may need to consider making strategic investments in higher education, particularly in research and development.

Adapting to Changes in Technology and the Economy:

Direction: A reevaluation of funding models for higher education is being prompted by the growth of online education, shifting labor markets, and shifting economic conditions. Governments and institutions are looking into ways to adjust funding strategies to these new circumstances.

Consideration: Future success will require adaptable funding models that encourage lifelong learning, reskilling, and the integration of technology into education.

In conclusion,

Funding models for higher education have a significant impact on the accessibility, quality, and sustainability of colleges and universities worldwide. There are benefits and drawbacks to each model, whether it is government-funded, tuition-driven, or a combination. Innovative funding strategies that support the diverse missions of higher education institutions and strike a balance between equity, accessibility, and sustainability are required as the landscape of higher education continues to change. Policymakers and educational leaders can contribute to ensuring that higher education remains a valuable and accessible resource for future generations by investigating new funding strategies and addressing existing obstacles.